ComparisonWithBooleanLiteralObserved

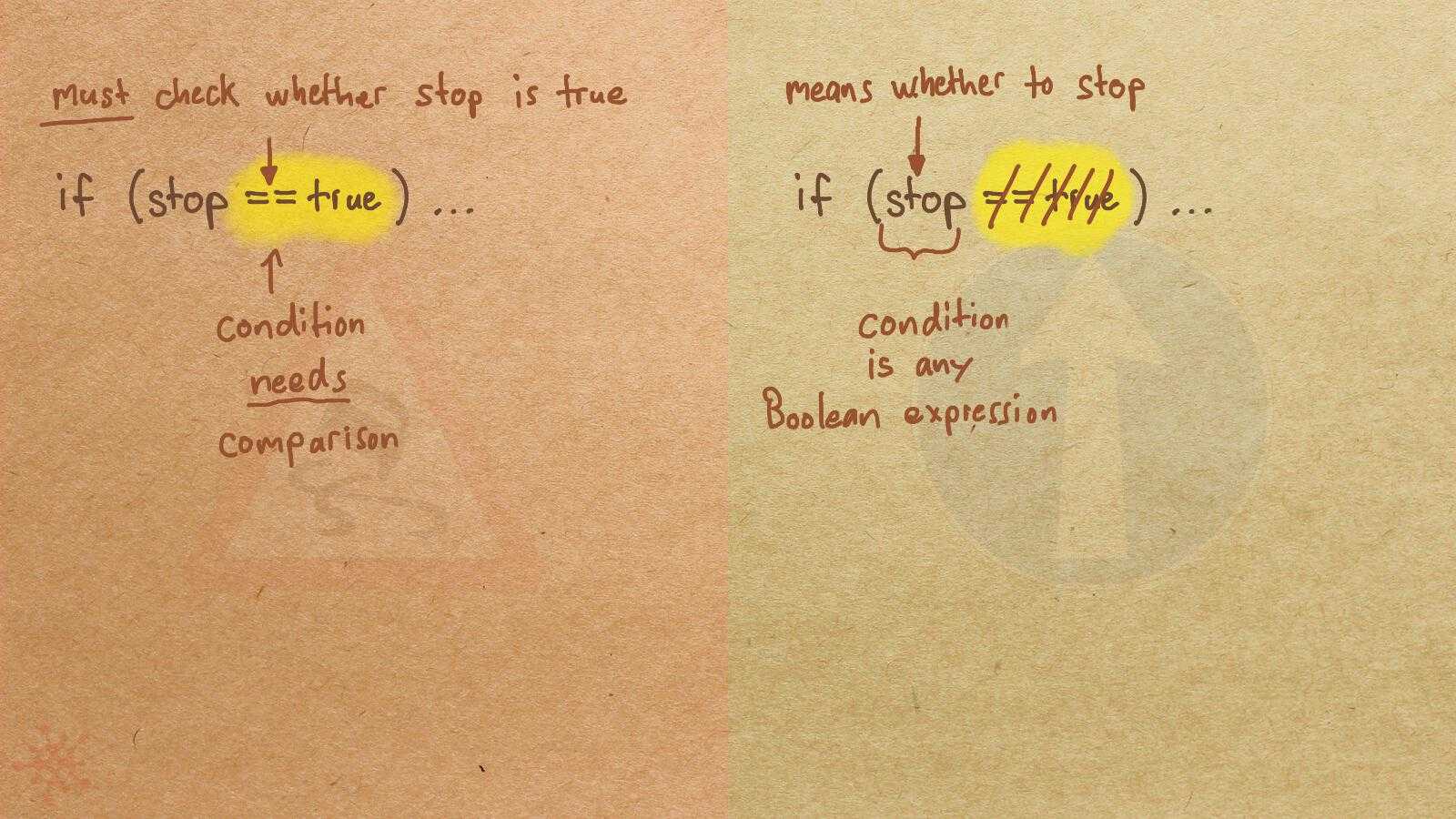

To test whether an expression is true or false, one must compare it to true or to false

To test whether an expression is true or false, one can just use it

CorrectionHere is what's right.

Such a comparison is entirely unnecessary.

if (CONDITION == true) {

...

}This can be simplified to:

if (CONDITION) {

...

}This applies to all uses of equality operators on boolean literals:

| Expression | Equivalent Simplified Expression |

|---|---|

e == true | e |

e == false | !e |

e != true | !e |

e != false | e |

Note that e is not just syntactic sugar for e==true.

Indeed, if a programmer writes e==true, a compiler will convert that to e.

Moreover, if e on its own would somehow be a convenient shortcut for e==true,

then one would have to convert e==true to (e==true)==true, ad infinitum.

The following two expression trees illustrate this point:

the simpler tree (with just the stop node)

actually appears within the more complicated tree,

and thus to deeply understand the complicated tree,

one would need to understand the simpler tree:

i.e., that it means to look up the value of variable stop,

which is going to produce the exact value we are looking for.

Argumentation

One may want to ask a student with this misconception which of the following two code snippets they prefer, and why:

System.out.println(age + 0);System.out.println(age);Then one can ask which of the following they prefer:

System.out.println(stop == true);System.out.println(stop);Finally one can discuss

what just writing age—and just writing stop—actually means.

One may also want to ask a student whether they would ever say “I am hungry is true” instead of just saying “I am hungry”. In a way, the former could be seen as a low-level statement, where one is concerned about “hungry” being a variable, while the latter is a higher-level statement, where “hungry” just means what it usually means.

While in our experience the above arguments do not always lead to a change in practice or attitude (i.e., students might continue to write explicit comparisons), we believe they help to provide a deeper understanding of expressions.

OriginWhere could this misconception come from?

This misconception may go back to textbooks and instructors using the term condition to describe what goes between the parentheses of conditional statments and loops.

if (CONDITION) { ... }

while (CONDITION) { ... }

for (...; CONDITION; ...) { ... }Students may thus assume that a condition is a separate syntactic construct, and is different from an expression. This may include assumptions that a condition must including a comparison, or that it must test whether a variable contains a specific value, or even that only a small number of very specific conditions are possible (i.e., that conditions cannot be arbitrarily composed the way expressions can be).

This misconception may also be enabled by explanations like the following (from Section 2.13 “Making choices: the conditional statement” in Objects First with Java):

if (perform some test that gives a true or false result) {

...

} else {

...

}Here, the wording “perform some test” may make students believe that the

condition is not just an expression, but a special kind of constructs (a test)

that possibly requires some testing operator (e.g., ==).

The wording “a true or false result” may make students believe

that they have to explicitly include true or false in the condition.

Note that this misconception is pretty much equivalent to the existing PMD Java design rule SimplifyBooleanExpressions. Thus, even professional developers seem to hold it.

SymptomsHow do you know your students might have this misconception?

We observed two kinds of symptoms: specific patterns in code, and specific explanations.

Code Patterns

In the following examples,

assume that CONDITION is some expression of type boolean

(e.g., isHappy, i < length, o != null, pacman.isHungry(), or a && b).

Condition

if (CONDITION == true) {

...

}Return

return CONDITION == true; // or return (CONDITION == true);Assignment

boolean b = CONDITION == true;Assignment, with negation

boolean b = CONDITION != true;Explanations

One explanation we observed was that

a condition like stop == true was considered to be more explicit,

and thus more easily understandable,

than the equivalent condition stop.

The reason given was that stop == true

would show that the program would go check

whether the variable stop contained the value true,

while the expression stop would not be as descriptive.

This explanation may imply a possible NoAtomicExpression misconception (i.e., that a variable name in isolation is not understood to be an expression).

ValueHow can you build on this misconception?

This misconception provides an opportunity to discuss

that conditions are expressions

(expressions of type boolean).

According to the Java Language Specification

“Boolean expressions determine the control flow in several kinds of statements”.

Moreover, it provides an opportunity to a discuss the power of composition, and how expressions can be composed of all kinds of subexpressions.

Language

Concepts

Expressible In

Related Misconceptions

Other Languages

Literature References

The following papers directly or indirectly provide qualitative or quantitative evidence related to this misconception.