ObjectsMustBeNamedObserved

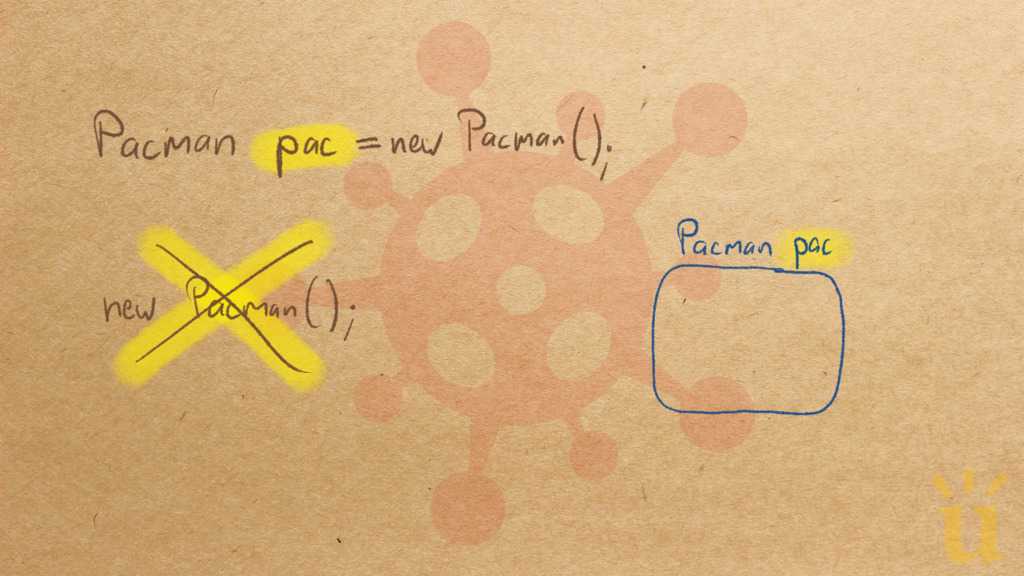

A variable is needed to instantiate an object

Objects have no name and can exist without a variable referring to them

CorrectionHere is what's right.

Writing new Object() on its own is perfectly fine.

It will allocate a new object and invoke its constructor.

If the expression stands on its own

(i.e., as a separate statement, like in new Object();),

then the resulting value, the reference to the allocated object, is thrown away.

Given that the constructor may have had a side effect, doing this can still be useful.

Reasoning by Analogy

Primitive Values Don’t Need To Be Named

Assume someone wrote the following code to print the negation of 5:

int a = 5;

System.out.println(-a);If their explanation was:

To work with the value

5I first have to give it a name. Only then can I negate it.

You would say:

Not really! You can directly negate the value, without first assigning it to a variable.

System.out.println(-5);And Objects Don’t Need To Be Named

The same reasoning that applies to values of type int

also applies to values of any other type,

including instances of classes.

For example, here we allocate an Object of type Person,

and then we invoke method getName() on it.

Person p = new Person("Kim"); // ObjectsMustBeNamed

System.out.println(p.getName());Note that new Person("Kim") is a value of type Person.

The above code can be refactored to:

System.out.println(new Person("Kim").getName());OriginWhere could this misconception come from?

Overgeneralization

This misconception may occur due to inappropriate generalization, if all examples of object allocations were embedded in initializations or assignments:

// declare a variable p and initialize it

Point p = new Point();// declare a variable p

Point p;

// assign a value to the variable p

p = new Point();Students might not be able to break down those statements into their constituent parts: an assignment with a variable on the left-hand side and an expression on the right-hand side.

Related to this, they might believe that there are NoAtomicExpression,

i.e., they might not understand that object allocations like new Point()

are expressions, and thus can be used within larger expressions.

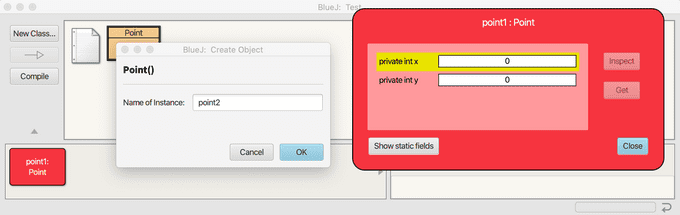

IDE

If students use BlueJ as their IDE, this may have triggered this misconception.

In BlueJ, objects are shown as red rounded rectangles.

All objects are labeled not just with their class (Point),

but with a name and the class (point1: Point).

Moreover, when a student interactively invokes a constructor,

BlueJ prompts them for the “Name of the instance”.

Textbook

The “Objects First with BlueJ” textbook includes UML-inspired diagrams where,

similar to the BlueJ IDE,

objects don’t just have a type, but also a name (notation: ”myDisplay: ClockDisplay”).

SymptomsHow do you know your students might have this misconception?

Students may:

not accept

new Object()as a legal expressionsay

new SomeAbstractClass();(whereSomeAbstractClassis an abstract class) is problematic because ”we didn’t assign it to anything — the right way would beNAME = new SomeAbstractClass();”exhibit CannotChainMemberToConstructor

say

new Integer(3) == new Integer(3)results in an error, because “you will need to assign some variable to it likeaorb, then do the same but with variablesa == b, and then it will be true”say ”allocate variable” instead of “allocate object”

label an object in a heap diagram not just with the class, but also with the name of some variable referring to that object

Language

Concepts

Expressible In

Related Misconceptions

Other Languages

Literature References

The following papers directly or indirectly provide qualitative or quantitative evidence related to this misconception.