AssignmentCopiesObjectObserved in Published Research

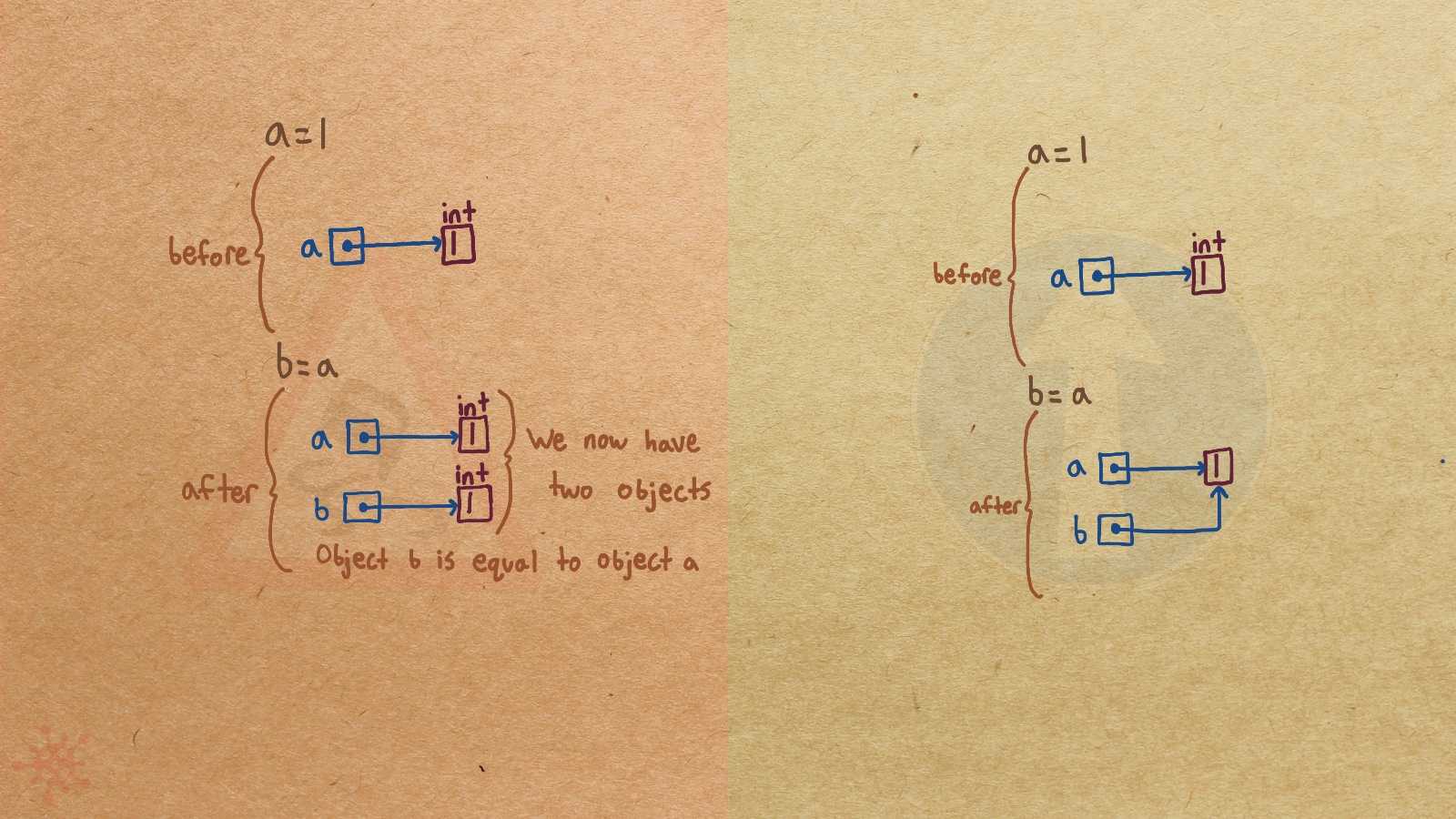

Assignment copies the object

Assignment copies the reference to the object

CorrectionHere is what's right.

An assignment to a variable copies the reference to the object, rather than creating a copy of the object and storing a reference to the new copy.

In Python, variables hold references to objects, not the objects themselves.

Consider the following example, assuming the existence of a class Sport:

table_tennis = Sport()

ping_pong = table_tennisThe first line of the above code creates a Sport object

and stores the reference to that object in the variable table_tennis.

The second line copies the reference that is stored in table_tennis into variable ping_pong.

At the end of this code, there is still only a single Sport object allocated in memory.

And there are two variables, table_tennis and ping_pong, that both refer to that same object.

This can be verified by calling the id function in Python,

which returns the “identity” of an object (e.g., its memory address).

The function returns the same value for both variables:

>>> id(table_tennis)

4345547472

>>> id(ping_pong)

4345547472OriginWhere could this misconception come from?

Python programs for complete novices often start by playing with immutable objects like integers or strings. For example, teachers may explain that an assignment to a variable “copies the number contained in the variable”. But variables do not directly “contain” objects: they store references.

When students later encounter mutable objects, this distinction becomes crucial.

SymptomsHow do you know your students might have this misconception?

Students may be puzzled about the behavior of their programs when they use assignments involving mutable objects like lists.

They may be unable to explain why “a modification to one variable” also “affects the other variable”, because they expect the two variables to be two independent objects in memory, and the assignment to create a copy.

ValueHow can you build on this misconception?

This misconception is a great starting point to discuss how “everything is an object” in Python. While the example above explicitly instantiates a custom class, values of built-in types like lists, dictionaries, and even integers are also objects in Python.

Therefore, assignments do not create copies of these objects either. For example:

first_list = [1, 2, 3]

second_list = first_listThe second line does not copy the list object (an operation sometimes referred to as “deep copy” or as “cloning”) but only copies the reference to the single list object in memory.

When an actual copy of the mutable object is needed, there are various ways to accomplish that in Python, depending on the type of object. For example, for lists, one can:

- Use the

copymethod of lists:second_list = first_list.copy() - Use the

listconstructor, providing the list to be copied as an argument:second_list = list(first_list) - Use the functions from the

copylibrary:or for a deep copy (i.e., recursively copying nested objects):from copy import copy second_list = copy(first_list)from copy import deepcopy second_list = deepcopy(first_list) - Use slicing:

second_list = first_list[:](arguably with a less clear intent)

Language

Concepts

Related Misconceptions

Other Languages

Literature References

The following papers directly or indirectly provide qualitative or quantitative evidence related to this misconception.

Quantitative systematic research

97 Swiss high school teachers and their students

Programming Language Misconceptions studied:

Quantitative systematic research

Students from 2 universities and other users of online textbook

Programming Language Behavior Misconceptions studied: